Nuclear Energy Activist Toolkit #47

The NRC’s regulations include requirements intended to prevent serious nuclear plant accidents from occurring and to mitigate one should it happen. Because these measures, even if fully and faithfully implemented, reduce rather than eliminate the chances of a serious accident, the NRC’s regulations also include requirements to protect the public from radioactivity released during an accident.

Fig. 1. (Source: Southern Company)

This post outlines the emergency planning requirements based on the plan for the Edwin I. Hatch Nuclear Plant in Georgia that UCS obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request. While the specific details of this plan vary a little from plans for other nuclear plants in the United States, the general framework applies to all plans.

What Emergencies Are Planned?

The NRC’s regulations provide for four emergency classifications, in increasing order of severity:

- Unusual Event

- Alert

- Site Area Emergency

- General Emergency

The classification level determines the extent of the response. In 2013, there were 29 Unusual Events declared and three Alerts. No more serious emergencies were declared in 2013 or in recent years at U.S. nuclear plants. The most recent Site Area Emergency was declared on February 20, 2006, after workers at the LaSalle nuclear plant were unable to initially verify that three control rods had fully inserted into the Unit 1 reactor core following an automatic shutdown.

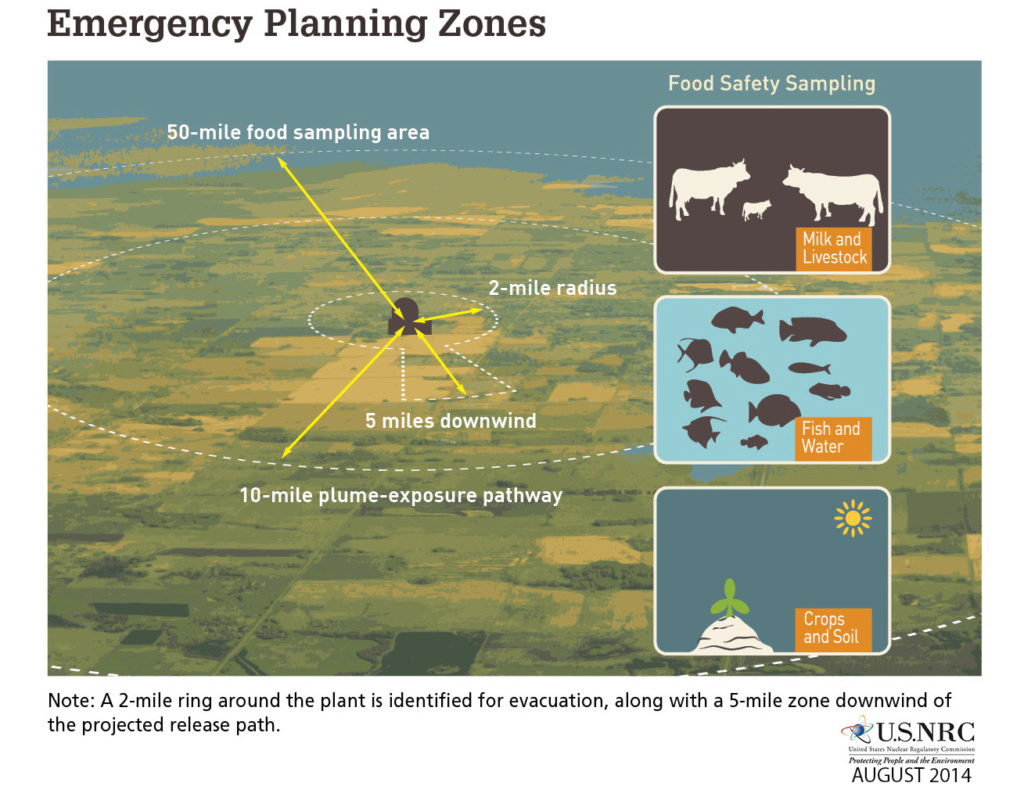

Fig. 2. (Source: NRC Information Digest 2014-2015)

How Are Emergencies Classified?

The NRC’s regulations require owners to develop formal procedures, accompanied by periodic training, for workers to use in monitoring plant parameters and classifying emergency levels.

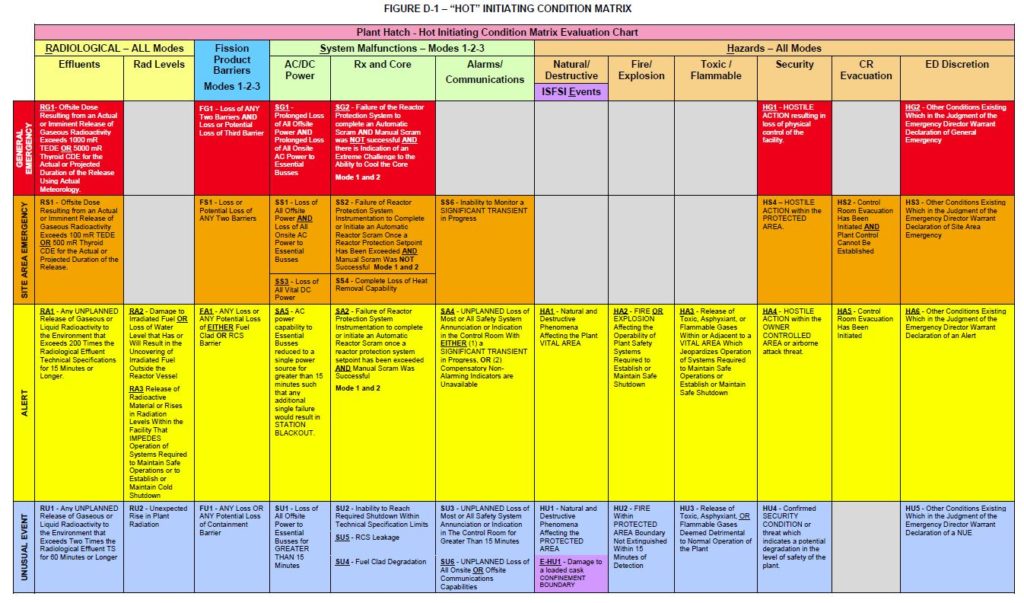

The matrix for classifying emergencies at Hatch is accompanied by considerable procedures and training to flesh out the cryptic nomenclature. But the matrix illustrates the concepts intended to reduce subjectivity and apply an appropriate response level hierarchy.

Fig. 3. (click to enlarge) (Source: Southern Company)

For example, the AC/DC Power column shows the emergency classification level increasing as plant conditions deteriorate. An Unusual Event, the lowest emergency classification, is invoked when power from the offsite electrical grid to essential in-plant electrical circuits is lost for longer than 15 minutes. NRC’s regulations require at least two onsite backup sources of power to essential electrical circuits. The emergency level escalates to an Alert when only one backup source is available. If that sole backup source is also lost, the emergency level escalates further to a Site Area Emergency. When the plant experiences a prolonged loss of both offsite and onsite electrical power, a General Emergency is declared.

An accident could result in multiple conditions, or boxes in the matrix, being applicable. The most serious condition dictates the emergency classification. In other words, when four Unusual Event conditions and only one Site Area Emergency condition are applicable, neither majority rule lets the emergency be classified as an Unusual Event nor averaging permit it to be an Alert. It is a Site Area Emergency.

Who Responds to an Emergency?

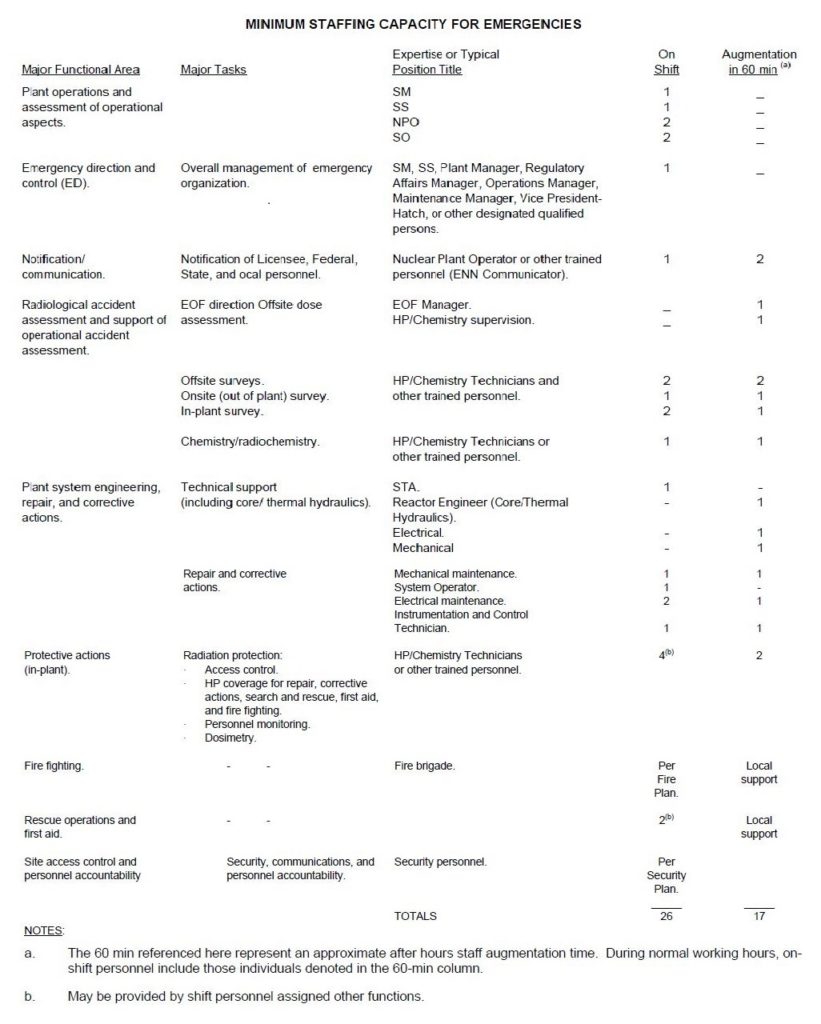

The initial response to a nuclear plant emergency is obviously by the plant’s workers. Because emergencies are not scheduled in advance, the NRC’s regulations include provisions for the minimum staffing levels needed to handle the initial response to an unscheduled emergency. (These minimum staffing levels were based on an assumption, proven invalid by the events at Fukushima, that an emergency would be limited to one reactor at a multiple-reactor plant like Hatch. One of the Fukushima lessons learned involves revisiting the minimum staffing levels to ensure that all needs can be handled during events challenging multiple reactors.)

Fig. 4. (click to enlarge) (Source: Southern Company)

The minimum staffing level for Hatch is similar to the levels at other nuclear plants. Hatch’s plan requires 26 on-shift personnel capable of being augmented by 17 others within an hour for a total of 43 individuals. Remember the infamous “Fukushima Fifty?” But Hatch’s total excludes quite a few security personnel. That minimum complement is defined by the NRC-approved security plan and is not specified because it could help bad guys figure out how many to include in any sabotage attempt.

The minimum staffing level handles Unusual Events, the least serious emergencies. As emergency levels increase, additional personnel are notified and directed to go to onsite or offsite locations to augment the response capability.

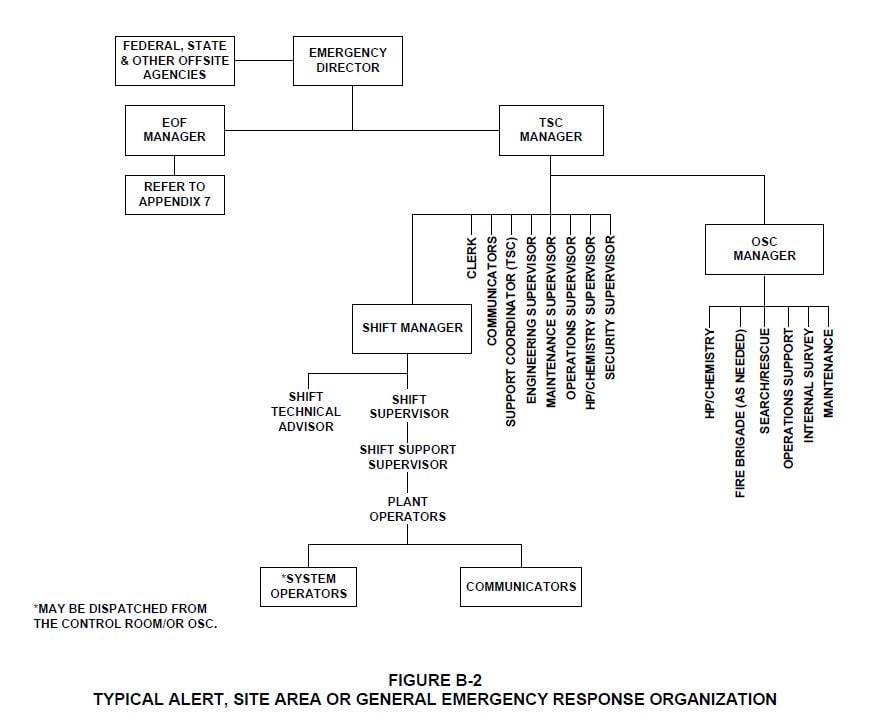

Fig. 5. (click to enlarge) (Source: Southern Company)

The Emergency Response Organization consists of an Emergency Director who oversees efforts at the Technical Support Center (TSC), Operations Support Center (OSC) and Emergency Operations Facility (EOF). The Emergency Director, a senior manager within the company owning the nuclear plant, is also the point of contact with local, state, and federal authorities who get notified during the emergency.

Workers in the Technical Support Center monitor plant conditions, assess trends, and make recommendations to the control room operators. The TSC staff also conducts research at its own initiative on to answer questions raised by the operators. For example, if cooling of the spent fuel pool has been lost, the TSC staff will estimate the decay heat load from irradiated fuel stored in the pool’s racks and calculate how long it will take for the pool’s water to heat up and boil.

Workers in the Operations Support Center repair broken equipment and/or install temporary backups. If a ventilation system problem causes the temperature inside a room containing sensitive electrical equipment to rise, the OSC staff will likely pursue parallel paths to fix the ventilation system and install portable fans to limit the temperature rise in the interim period.

Workers in the Emergency Operations Facility handle surveys of air, water, and soil around the nuclear plant and perform radiation dose assessments. The EOF staff also coordinates with the company’s public information staff to communicate with the media about the emergency.

Communications between emergency responders is vitally important due to the large number of changing conditions that are often involved. Wind speed and direction can change. Plant operations, such as opening or closing a containment vent pathway, can change.

Fig. 6. (click to enlarge) (Source: Southern Company)

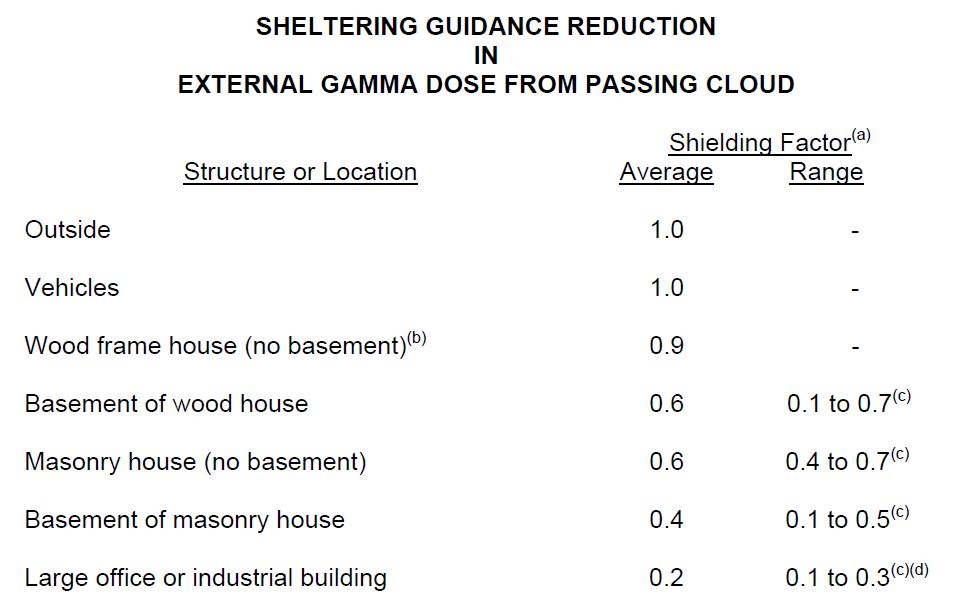

The emergency plan consists of voluminous documents and extensive training to assist responders adapt to so many variables. This table from Hatch’s emergency plan illustrates the guidance that is available to responders. It shows the relative value of sheltering options for protecting people from radiation exposure as a radioactive cloud passes by them. Individuals who are outside or in cars receive no protection. An individual inside a wood frame house receives only 90 percent (0.9) of the radiation exposure that he or she would receive if outdoors. If able to go down into the basement of a wood frame house, the person receives only 60 percent of the radiation exposure received outdoors. This guidance, coupled with projections about timing of releases of radioactivity from the plant and time needed to evacuate downwind communities is factored into public health recommendations.

What Do Emergency Plans Protect?

Emergency plans are intended to protect plant workers and the public from harm caused by exposure to radiation.

Fig. 7. (click to enlarge) (Source: Southern Company)

Workers are protected by measures such as limits on how much radiation exposure they can receive during an emergency. Normally, workers are limited to 5 rem per year. (For context, the NRC defines a lethal dose of radiation as that expected to cause half of the exposed population to die within 30 days and estimates that dose to be 400 to 450 rem.) During an emergency, workers can be directed to undertake tasks that could expose them up to 10 rems to protect equipment or up to 25 rem to save co-workers or protect the public. But workers cannot be directed to perform a task during an emergency that would expose them to greater than 25 rem unless they volunteer to do it.

The emergency plans protect people living around a stricken nuclear plant in different ways. The emergency plans assume that the “keyhole” population—people living within two miles of the plant and up to five miles directly downwind from it—will require evacuation (see the dotted figure in the center of Fig. 8). People living outside of the “keyhole” but within ten miles may also require protection either in the form of evacuation or sheltering depending on numerous factors. The emergency plans provide for sampling crops, cattle, water supplies, and other food sources out to 50 miles from the plant to protect the public from the ingestion of radioactivity. Because wind directions change and wind does not stop after 10 or 50 miles, these emergency plan boundaries are supposed to be starting points rather than boundaries. The “keyhole” will rotate and the 10-mile plume-exposure pathway will accordion outward if necessary.

While the plant’s owner and the NRC can make recommendations about sheltering or evacuating members of the public, those decisions are reserved for local and state officials (i.e., the Governor).

How are Emergency Plans Checked?

The NRC’s inspectors periodically evaluate the emergency plans as part of the Reactor Oversight Process. It’s not merely one, two, or even three inspections, but a suite of inspections that cover the various elements of the emergency plan.

And at least once every two years, a large-scale exercise of the emergency plan is conducted. The NRC’s inspectors are onsite to observe how well plant workers perform their assignments under the emergency plan while the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) grades how well local, state, and federal authorities discharge their response duties. NRC inspection findings, if any, fall under the Emergency Preparedness cornerstone of the Reactor Oversight Process while FEMA issues an exercise report documenting its findings.

A few years ago, the NRC invited me to observe one of the biennial emergency exercises from its Operations Center at its headquarters offices in Rockville, Maryland. The NRC’s Operations Center is staffed 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The picture shows a portion of the Operations Center during the biennial exercise conducted April 29, 2014, for Fermi Unit 2 near Monroe, Michigan.

Bottom Line

Emergency plans supplement the protection workers and the public receive from the NRC’s regulations intended to prevent serious nuclear plant accidents. To increase the value from this defense-in-depth layer, the NRC should consider:

- Periodically testing the effectiveness of public notifications: The biennial exercises evaluate how well the plant owner interfaces with local, state, and federal authorities to protect the public from radiation released during simulated accidents. There’s always one entity missing from the exercises—the public. It’s assumed that if the emergency sirens wails, all the public will hear them. It’s assumed that all the public will know precisely what to do upon hearing the sirens. Plant workers along with local, state, and federal authorities have to be trained and periodically rehearse their emergency planning roles while the untrained public is assumed to be 100 percent reliable without any practice. Those same members of the public must be instructed how to fasten a seatbelt on an airplane or don a life vest on a passenger ship, yet are assumed capable of grasping the proper response to a nuclear plant disaster without any prompting or coaching or preparation whatsoever. That’s just goofy.

- Periodically rotating the “keyhole” and expanding the 10-mile emergency planning zones: It is assumed that existing emergency plans can be readily and easily expanded as necessary to handle changing conditions. It would be useful to demonstrate this flexibility through periodic testing, particularly when expansion brings a new county, large city, or state into the mix. It’s not anticipated that periodic expansions will be showstoppers, since local and state authorities routinely coordinate with each other during real non-nuclear events.

- Periodically simulating disagreement with State’s decisions on protective measures: While monitoring the situation at Fukushima, the federal government decided that conditions warranted more protection for U.S. citizens in the area than had been taken by the Japanese government. Thus, the federal government recommended that U.S. citizens within 50 miles of Fukushima evacuate the area. It would be useful during some of the biennial exercises to simulate disagreement between the federal government (i.e., NRC) and the State government about actions necessary to protect the public. Such simulations would road test how disagreements would either be resolved or handled. They would answer key questions like would the NRC publicly air its disagreement with the Governor?

Emergency plans are a valuable element in the defense-in-depth approach to nuclear plant safety. Whenever possible, their value should be enhanced.

The UCS Nuclear Energy Activist Toolkit (NEAT) is a series of post intended to help citizens understand nuclear technology and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s processes for overseeing nuclear plant safety.