Disaster by Design/Safety by Intent #23

Disaster by Design

Among the actions taken by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in response to the March 11, 2011, accident at Fukushima was to issue an order on March 12, 2012, to all U.S. nuclear plant owners requiring them to procure equipment and implement measures to enable their facilities to cope with an extended loss of normal and backup power supplies to emergency equipment.

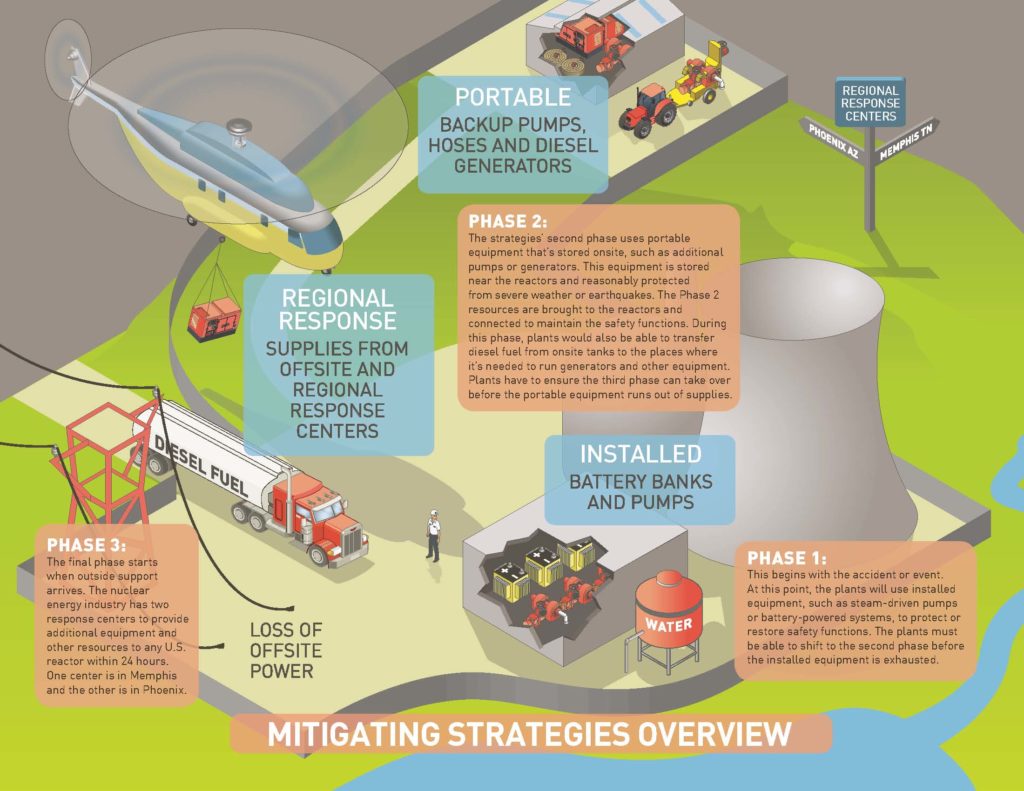

Fig. 1 (Source: NRC)

The NRC required that owners develop a phased response capability (Fig. 1). The initial response is by permanently installed equipment. Recognizing that this equipment may become unavailable (as happened at Fukushima), the NRC required a followup response capability by portable equipment stored in places not likely to be affected by the accident. Recognizing that portable equipment provides an interim response, the NRC required a longer term response capability to be provided by the “nuclear cavalry” (equipment and staffing resources arriving from offsite locations). The Nuclear Energy Institute developed the Diverse and Flexible Coping Strategies (FLEX) Implementation Guide for use by plant owners in complying with the NRC’s order.

Safety Detour?

There can be a big difference between the course plotted and the road taken. For example, a family heading out by car from their home in Atlanta, Georgia for a relaxing vacation on Sanibel Island in Florida should become a little troubled upon seeing the Washington Monument through the windshield.

If the following examples are any indication, the road to the Fukushima fixes ordered by the NRC might have taken a detour or three.

Pilgrim

Winter storm Juno made an unwelcome visit to the Pilgrim nuclear plant in Massachusetts in January 2015. The storm disconnected the plant from the offsite electrical grid, its normal source of power. The emergency diesel generators automatically started and supplied power to emergency equipment. Wanting to use some non-emergency equipment, workers fetched a portable air compressor from the onsite FLEX warehouse. They connected it all up and turned it on. But FLEX proved inflexible.

The portable air compressor produced air at a pressure of about 80 pounds per square inch. The equipment the workers wanted to use required an air pressure of nearly 100 pounds per square inch to operate. Instead of aiding the response, the FLEX thing turned out to be merely a noisy time-waster. (See the 52nd page of the 68 page report by the NRC on the Pilgrim event.)

River Bend

The response to an extended loss of normal and backup power requires cooling for more than just the reactor core. The control room and other areas of the plant require cooling too. Not just to keep the workers comfy, but also to prevent electrical equipment such as switches, relays, and gauges from overheating damage. How quickly control rooms and other vital areas heat up after the air conditioning is lost must be determined to allow informed decision-making about prioritizing the manual actions undertaken by a small group of workers during a big challenge.

Workers calculated that it would take nearly 24 hours for the control room at the River Bend nuclear plant in Louisiana to heat up from 65°F to 104°F following an air conditioning loss. That provided ample time for workers to install portable fans from the FLEX warehouse for backup cooling.

But an event at River Bend in March 2015 demonstrated the calculation to be a wee bit optimistic. After air conditioning was lost during this actual event, the real temperature of the control room rapidly heated up to 91°F in about half an hour. Workers did not have a day to install portable fans as the FLEX plan indicated—they had about an hour. Oops! (See the 59th page of the 78 page NRC report on the River Bend event.)

Arkansas Nuclear One

The one-two punch from an earthquake and a tsunami caused the Fukushima disaster. The NRC ordered plant owners to visually inspect their facilities for earthquake and flooding vulnerabilities. Workers completed the mandated walkdowns at Arkansas Nuclear One and informed the NRC, in writing on November 17, 2012, that no major protection deficiencies or vulnerabilities were found.

They must not have looked very hard.

On March 31, 2013, a 550-ton stator was dropped while being lifted in the Unit 1 turbine building. The dropped load ruptured pipes in the area. Water got into areas it should not have reached through openings in flood barriers that should not have existed. When workers visually inspected the plant—again—after this event, they now found literally dozens of deficient flood protection measures. (See one of several NRC reports on the Arkansas Nuclear One event.)

If areas of the plant flooded that were supposed to be protected from this hazard, workers may not be able to use the FLEX equipment. They might not be able to travel through flooded rooms to connect the FLEX components. Or, the equipment to be powered from a FLEX portable generator could be submerged by the flood waters and disabled.

Safety by Intent

The NRC had the best of intentions when it ordered plant owners to implement Fukushima fixes.

Fig. 2 (Source UCS)

The owners had the best of intentions when they procured millions of dollars of portable equipment and built massive warehouses to store it all.

There’s a saying about the road to hell being paved with good intentions. (Hey, is that the Washington Monument over there?)

Actual events, not reviews by plant workers or NRC inspectors, have revealed big ol’ holes in the FLEX safety net.

Fukushima had a sea wall for protection against tsunamis. It worked just fine for nearly four decades, until a tsunami arrived. The protective sea wall was long enough, but not high enough.

For the NRC’s Fukushima fixes to reach their target destination, the NRC must determine why Pilgrim procured an inadequate FLEX air compressor, why River Bend thought it had 24 hours to handle a one-hour problem, and how dozens of flood protection problems remaining invisible during the NRC-mandated walkdowns at Arkansas Nuclear One.

Too much is at stake for U.S. nuclear plants to be protected from an extreme natural event—unless an extreme natural event occurs.

—–

UCS’s Disaster by Design/ Safety by Intent series of blog posts is intended to help readers understand how a seemingly unrelated assortment of minor problems can coalesce to cause disaster and how effective defense-in-depth can lessen both the number of pre-existing problems and the chances they team up.