The reaction of missile defense advocates to the START treaty and their claims that the administration is limiting defenses shows how volatile the issue of missile defense remains in U.S. politics. So it’s not surprising the administration laid out an ambitious missile defense plan last September when it replaced the Bush missile defense plan for Europe, hoping to mute such criticism.

But the administration’s plan is likely to cause problems down the road—if not sooner—for issues the administration clearly cares about: deep reductions in nuclear arsenals and stable relations with Russia and China.

The administration’s plan,  based on the Aegis sea-based missile defense system, seems to have gained some acceptance even among traditional missile defense skeptics for two reasons. First, Aegis is seen as the missile defense system that “works” since its test record is better than that of the Ground-based Missile Defense (GMD) system fielded in Alaska and California. Second, a system based on Aegis is seen as unlikely to cause strategic problems with Russia and China. This is because the current Aegis interceptor (“SM-3 Block IA”) is relatively slow and is designed to intercept missiles with ranges of 1,000-1,500 km, which is much shorter than intercontinental range missiles.

based on the Aegis sea-based missile defense system, seems to have gained some acceptance even among traditional missile defense skeptics for two reasons. First, Aegis is seen as the missile defense system that “works” since its test record is better than that of the Ground-based Missile Defense (GMD) system fielded in Alaska and California. Second, a system based on Aegis is seen as unlikely to cause strategic problems with Russia and China. This is because the current Aegis interceptor (“SM-3 Block IA”) is relatively slow and is designed to intercept missiles with ranges of 1,000-1,500 km, which is much shorter than intercontinental range missiles.

Unfortunately, both of these perceptions are wrong.

First, while the Aegis system has worked well in tests, those tests say essentially nothing about how the system would “work” against a real-world attack. Aegis, like the GMD system, is intended to intercept above the atmosphere, which is also where it can be fooled by decoys and other countermeasures that any country that can build a ballistic missile and nuclear warhead could and would add to its missiles. None of the Aegis tests have included realistic countermeasures.

(There is also a common misperception that the Aegis system can intercept during boost phase, when the missile’s engines are still burning, if it’s based close enough to the launch site. However, the SM-3 interceptor does not have the speed, maneuverability, or sensors to intercept in boost phase, and that capability is not planned for the follow-on systems either.)

Second, in its September announcement the administration laid out an ambitious ten-year plan that would lead, if successful, to a large, globally based missile defense system with faster interceptors intended to destroy long-range missiles. In fact, according to the Chinese press, the main significance of the announcement was that it demonstrated a long-term U.S. commitment to missile defense.

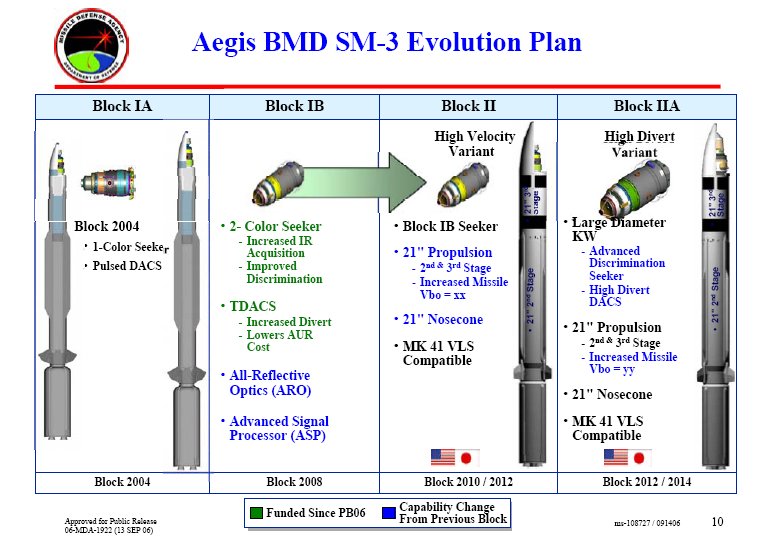

The specifics of the U.S. plan are likely also a concern to China. Current plans are to equip a large number of ships with the Aegis missile defense system, raising the number of such ships from fewer than 20 now to nearly 70 within a few years. And the faster, next-generation Aegis interceptors currently being jointly developed with Japan (see diagram) are designed to be launched from the same launch tubes on these ships. Since each ship could in principle carry more than 100 interceptors, China could easily see this as building the base for fielding many hundreds or thousands of mobile, strategic-capable interceptors.

Such a view was likely reinforced by comments at the September 17 press conference by Secretary of Defense Gates and General Cartwright, vice-chair of the Joint Chiefs. They noted repeatedly that the goal is to develop a global network of mobile interceptors and sensors. Cartwright said explicitly that the goal was to have “a sufficient number of ships to allow us to have a global deployment of this capability on a constant basis, with a surge capacity to any one theater at a time.”

Some may question why, if countermeasures can foil Aegis interceptors, China would worry about these defenses. The answer is that while Chinese scientists understand the countermeasure issue, Chinese political and military leaders likely do not—just as many U.S. political and military leaders apparently do not. China will therefore likely build decoys but also take other measures in reaction to the system. As a result, U.S. plans may be affecting decisions Chinese military planners are making now about the scope and pace of Chinese nuclear modernization. They may also sour China’s view of a Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty, which would limit the number of warheads it could build in the future.

Moreover, Chinese analysts have told us there is an additional concern about this system. The current Aegis interceptor has a demonstrated ability to intercept satellites. In fact, since satellites don’t carry countermeasures, current missile defense tests are more relevant to intercepting satellites than intercepting missiles. While the current Aegis interceptor could only reach satellites at low altitudes, the next-generation interceptors could reach satellites throughout low Earth orbit. The deployment of a large number of mobile interceptors that could be moved to optimal locations for attacking particular satellites would be seen as a significant defacto anti-satellite capability

Some within the administration are no doubt aware of all these issues. It would be ironic if the administration’s real steps to reduce nuclear threats to the United States were derailed by its pursuit of a system that has yet to undergo realistic testing. If the administration believes developing such a missile defense system is important, then it needs to have an equally ambitious plan for mitigating the potential reactions of Russia and China to such a system.