In the next few days, the Pentagon is expected to officially release its latest annual report by the Director, Operational Test and Evaluation (DOTE) on the testing programs of a wide range of military systems. The most politically charged of those covered in the report is missile defense, which currently has a budget of about $10 billion per year.

This report will give some sense of how seriously the Pentagon is currently taking its responsibility to develop systems that work in real-world situations, and to use rigorous testing to weed out those that don’t.

For many years, the development of U.S. missile defense systems has proceeded with too much optimism and too little serious testing. Over the past decade, the U.S. land-based missile defense system—the so-called Ground-based Midcourse Defense (GMD)—has not faced any realistic flight tests. Even so, it has not done well in those tests.

Both the Bush and Obama administrations have made rosy but false claims of capability despite a lack of real-world test results to back up those claims. Even under the Obama administration, the approach to missile defense has so far been long on rhetoric and short on rigor.

For example, the administration’s long-awaited Ballistic Missile Defense Posture Review, released in February 2010, made the unsubstantiated claim that the United States “is currently protected against the threat of limited ICBM attack” by the GMD system. The U.S. has been developing GMD for more than a decade with the goal of shooting down long-range nuclear missiles in flight during the middle phase of their trajectory. Despite the lack of realistic testing, the U.S. has fielded 30 interceptors—26 in Alaska and 4 in California—and Congress has given money for more.

Moreover, last year’s DOTE report said that ground and computer tests “suggested GMD provided a capability to defend the United States against limited numbers of long-range ballistic missiles with uncomplicated, emerging threat warheads.”

Here the phrase “uncomplicated, emerging threat warheads” means warheads with no or very simple decoys or other countermeasures. But no knowledgeable person really expects that is the threat the defense would face in a real attack. Even the BMD Posture Review notes that “some states are working to defeat missile defenses, through both technical and operational countermeasures.” The U.S. intelligence community put it more clearly in its 1999 National Intelligence Estimate, stating:

We assess that countries developing ballistic missiles would also develop various responses to US theater and national defenses… Many countries, such as North Korea, Iran, and Iraq probably would initially rely on readily available technologies… These countries could develop countermeasures based on these technologies by the time they flight test their missiles.

What this means is that if a country decided to fire a missile at the U.S., it would presumably make that attack as complicated as possible, and would have the ability to do so.

Interestingly, the phrase “uncomplicated, emerging threat warhead” seems to have replaced the phrase “threat-representative warhead” that the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) used in the past. This may reflect the Pentagon’s admission that the “uncomplicated” warheads it is testing the GMD system against don’t really represent the threat it would expect to see in an actual missile attack.

The GMD flight tests may be appropriate for a system that is still in relatively early stages of development, which this one is. But since the GMD system has not been tested against realistic threats, any statements about how well it would work in defending the U.S. from an attack are irresponsible speculation. They have no place in an official document like the BMD Posture Review.

What Do the GMD Tests Show?

Leaving aside the claims about the capability of the system, what do the flight tests of the GMD system actually show? After all, flight tests in which the interceptors attempt to destroy mock targets are the physical data on which claims about the capability of the system should be based.

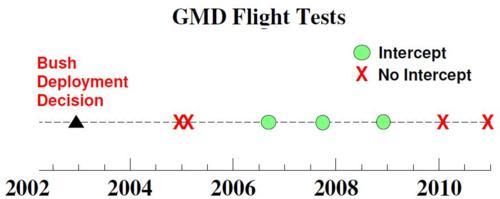

President Bush decided in December 2002 to start fielding the GMD system. Presumably that indicated an assessment that the technology was ready. One would still have expected a concerted flight-testing effort to make sure.

But in the more than 8 years since then, there have been only 7 GMD flight tests—fewer than one a year. And 4 of those 7 tests have failed to get an intercept. So even in tests against “uncomplicated” threats under controlled conditions and with no realistic decoys, the system has demonstrated only a 43% chance of hitting its target.

(Including the early GMD tests leading up to the deployment decision, the overall record is 8 of 15.)

Moreover, in the past two years there have been 2 flight tests of the GMD system, both of which have failed. And these are the interceptors the Pentagon says are “operationally deployed” and ready for action.

So What’s Going On?

Developing an effective missile defense system requires two essential steps.

The first step is developing a reliable technical capability to “hit a bullet with a bullet,” that is, to have sensors that can identify and track an incoming warhead, plus an interceptor that can use that information and its on-board sensors to home on the warhead accurately enough to physically run into it and destroy it. This is a demanding technical task, but it is in principle achievable to some level of reliability.

This is still what the tests are testing—the ability to home on and hit an identified target. As noted above, the GMD system has only been able to do this 3 times out of 7 attempts in the past 8 years, despite being tested under controlled conditions.

And yet the second step is the much harder step. The system needs to be able to reliably identify the warhead in the cloud of many objects it may face. This step is particularly difficult since it is not a purely technical problem—the attacker is actively doing everything it can to fool the defense. For example, the defense is unlikely to know before an attack what the warhead will look like to the interceptor’s sensors because it can be readily disguised.

Even if the system could accomplish step 1 flawlessly, the difficulty of step 2 could keep the system from destroying any warheads. Testing whether the system can handle step 2 has not started yet. (The Aegis missile defense system the U.S. is developing has done better in tests of step 1, but its ability to accomplish step 2 has not been tested, and it will run into the same countermeasure problem.)

So why would anyone make such inflated claims about the system?

Much of this is purely political rhetoric. And some of it may have to do with hoping that inflated claims about the capability of the system will add to deterrence.

But claims about a military capability that does not in fact exist are dangerous—because military and political leaders might believe those claims. The administration must ensure that it has in place a rigorous testing program for missile defense. And then it has the responsibility to tell the truth about that system based on those tests.