President-elect Trump named Peter Navarro to head the as-yet-uncreated White House National Trade Council. What does this portend?

Michael Wessel, a long-serving member of the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission (USCC), argued the United States government needs “to put somebody in charge” of US China policy “who looks at both the economic and national security implications of the US-China relationship and recognizes that they are inextricably intertwined.” Navarro definitely fits that description.

Navarro’s China: “The Planet’s Most Efficient Assassin”

It is not clear what this council will do or how it might influence US-China relations. What is clear is that Dr. Navarro believes that trade with China is a zero-sum game the United States is losing. Moreover, the Harvard-educated economist also believes that “an authoritarian and increasingly militaristic China” is using its supposed trade advantage to execute “a hegemonic agenda” that could lead to a nuclear war with the United States.

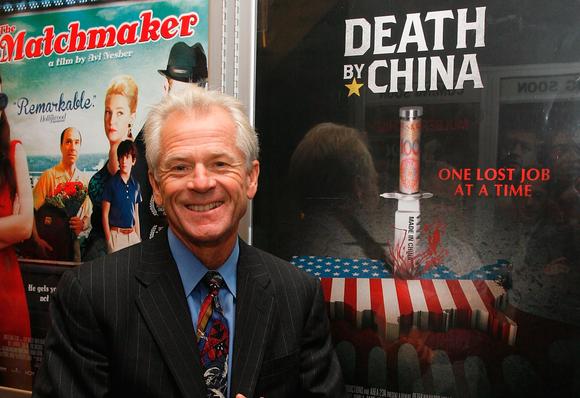

Dr. Peter Navarro pictured next to a poster advertising a film based on his book: Death by China.

Dr. Navarro authored a trilogy of books that articulate his view of the “inextricably intertwined” relationship between the China trade and the possibility of nuclear war. In those books he argues that China is “the greatest single threat facing the United States” and that “every ‘Walmart dollar’ we Americans spend on artificially cheap Chinese imports” increases that threat. He describes China as a “budding colonial empire” with “lethal appetites” for energy and raw materials that are feeding “the extremely rapid and often chaotic industrialization of the most populous country on the planet.” Most importantly, he argues that China’s rapid modernization has “put it on a collision course with the rest of the world.”

Navarro writes that unless this course is altered the United States and China are “inexorably headed for conflict—and perhaps even a nuclear cliff.” He claims that China “now houses a rapidly growing arsenal of nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles” that are aimed at the United States and most of China’s neighbors, including non-nuclear weapons states like the Philippines and Vietnam. He suggests China may already have thousands of such missiles hidden in an “underground great wall.” Alarmingly, Navarro seems convinced that China’s leaders would “opt for nuclear war” and “ride things out in China’s many bomb shelters” if they cannot prevail in a conventional conflict with the United States.

Few economists would agree that all the benefits of the global China trade accrue to one side, or, in Navarro’s words, that “China has boomed at the expense of much of the rest of the world.” To the contrary, many believe China’s economic development is now the single greatest contributing factor to global economic growth.

Similarly, Navarro’s characterization of China’s nuclear capabilities draws on a discredited analysis based on questionable sources and methods that are not accepted by US intelligence agencies or security experts.

Nevertheless, his appointment suggests he has the confidence of President-elect Trump, who seems to be using the transition period to signal a dramatic shift in US China policy.

Implications for US China Policy

Navarro’s prescription for change is a policy of economic and military containment. It is based on the following diagnosis from University of Chicago professor John Mearsheimer.

“What really makes China so scary today is the fact that it has so many people, and it’s also becoming an incredibly wealthy country so that our great fear is that China will turn into a giant Hong Kong. And if China has a per capita GNP that’s anywhere near Hong Kong’s GNP, it will be one formidable military power. So a much more attractive strategy would be to do whatever we can to slow down China’s economic growth – because if it doesn’t grow economically, it can’t turn that wealth into military might and become a potential hegemon in Asia.”

Navarro anticipates that US allies, and US consumers, will oppose containment because of the economic costs, which would be higher prices for US consumers and significant disruptions to Asia’s economy. But he believes he can eventually persuade the people of the United States and the policy-makers of Asia that trading with China is equivalent to “helping to finance a Chinese military buildup that may well mean to do us and our countries harm.”

Given this, it is not unreasonable to expect that Dr. Navarro will use the bully pulpit of the White House National Trade Council to make this case for an economic boycott of China.

On the military side Navarro imagines the United States can only keep the peace if it is able to work with its allies to “demonstrate a collective level of capabilities that, on the one hand, are not directly threatening to China, yet on the other hand are unassailable by any imaginable display of Chinese force.” He recommends “using attack submarines” to build an “undersea Great Wall” on China’s periphery. Navarro also supports the deployment of “substantially larger numbers” of “both the F-35 fifth generation fighter and the new Long-Rang Strike Bomber.” Most importantly, he argues that the Chinese leadership must be made to believe that the United States has the “will and resolve” to “use nuclear weapons if they must” to stop conventional Chinese aggression.

It is difficult to believe that China would not find these recommendations “directly threatening.” While the new trade council Navarro will lead is unlikely to deal with military issues, his views may still influence the thinking of others within the administration.

How Might China Respond?

Should the Trump administration act on Dr. Navarro’s recommendations for a policy of economic and military containment, it will most likely strengthen the credibility of China’s defense and foreign policy analysts who perceived the Obama administration’s “pivot to Asia” as a means of containment. To them, Navarro’s recommendations are a logical acceleration of an already well established anti-Chinese drift in US policy.

Chinese voices who argue for greater engagement with the United States—and greater accommodation of US concerns— are more likely to be marginalized.

US exporters, especially those in the technology sector, are likely to be effected by increased Chinese efforts to make their economy less reliant on the United States. Already substantial Chinese domestic investment in indigenous technical development is likely to increase.

The Chinese space program offers an interesting guide to the potential consequences. Many of the same US China analysts Dr. Navarro cites in his books were associated with US congressional efforts in the late 1990s to block US contact with the Chinese space community. The restrictive policies they enacted grew more severe over the past two decades. Yet, during that time China made dramatic advances in space science, technology and applications. It also expanded its relationships with other international partners, such as the European Space Agency. US efforts to “contain” the Chinese space sector arguably made it stronger than it otherwise might have been by stimulating the development of domestic Chinese capabilities and alternative international partnerships.

China is unlikely to be overly concerned about Navarro’s recommendations on credible US nuclear threats. For the time being, at least, Chinese strategists assign one and only one purpose to China’s nuclear forces, which is to prevent a nuclear attack on China. Traditionally they have believed that the requirements for preventing such an attack are rather low. Retaliation with as little as a single Chinese nuclear strike against one US city is believed to be enough to deter any US president from attacking China with nuclear weapons.

Navarro, and others around President-elect Trump, may put great stock in the strategic value of his unpredictably but this is unlikely to shake China’s faith in the deterrent effect of its potential to retaliate.

Chinese adaptations to any changes in the US nuclear posture will be focused on assuring the ability of its nuclear forces to survive a US first strike. That may include a modest increase in the size of China’s nuclear force. But one of the more troubling proposals already under consideration is upgrading the alert status of China’s forces so they can be launched on warning on an incoming US attack. The early warning systems needed to implement such a policy are known to give false warning, especially in the early years of their operation.

Navarro’s recommendations, if acted upon, could cause Chinese leaders to expedite the development and deployment of an early warning system, increasing the risk of an accidental or mistaken Chinese nuclear launch against the United States.